True Colors at Albertina Modern Captures a Century of Innovation

Colour photography feels like a given in today’s world, but it was a long and intricate journey to get here. Albertina Modern’s exhibition True Colours traces this fascinating evolution from 1849 to 1955, showcasing around 130 works that document the relentless pursuit of capturing the world in colour. As a passionate observer of photography, I recently visited the exhibition with fellow members of my photo club. I especially loved the delicate, almost dreamlike pictorialist photographs that felt like paintings frozen in time.

The Early Days: Hand-Coloured Daguerreotypes and Pigment Prints

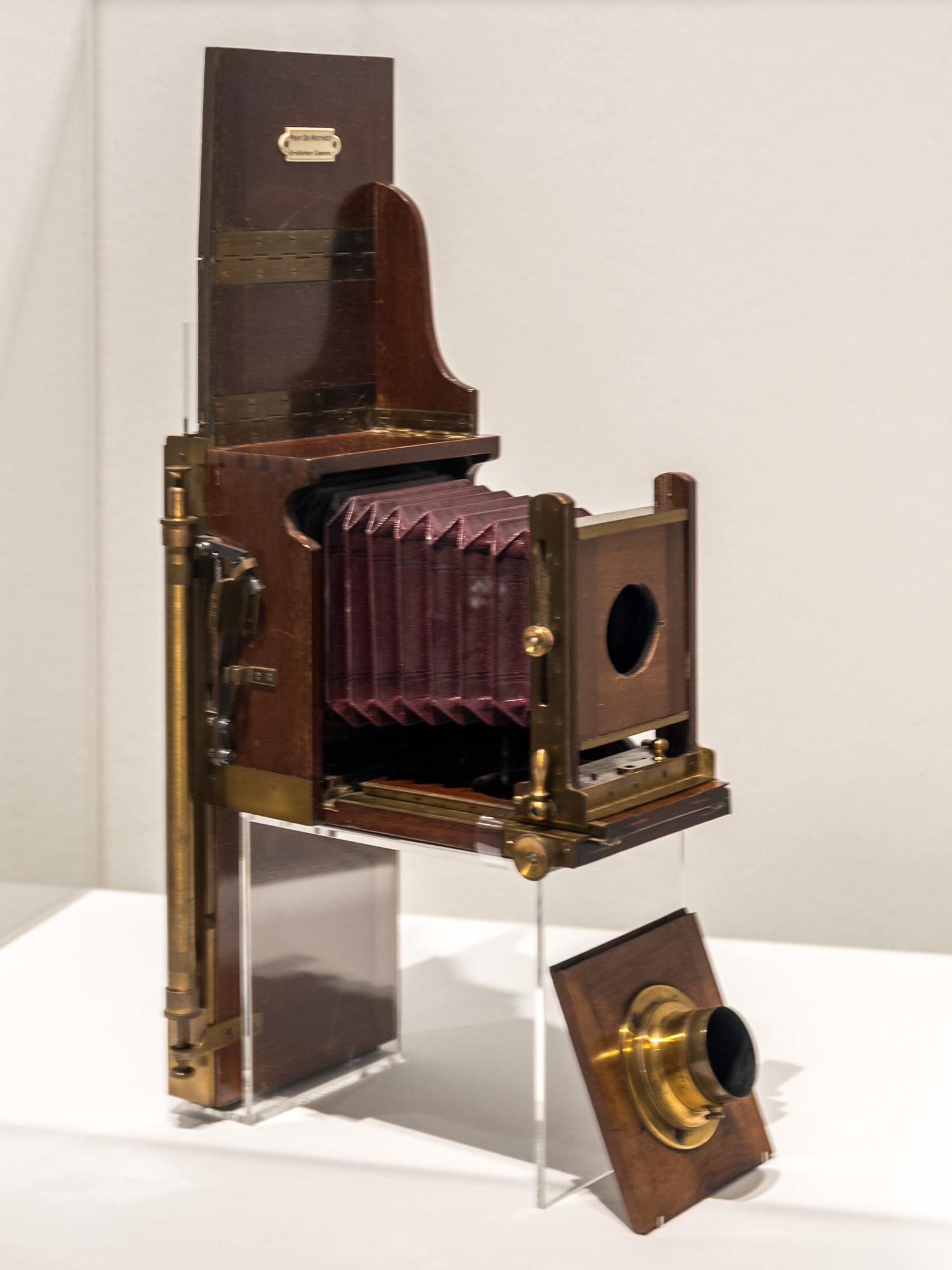

Before film technology could render the world in colour, early photographers relied on meticulous hand-colouring techniques. The first commercially successful photographic process, the daguerreotype, was developed by Louis Daguerre in 1839. These images, though stunning in their detail, were monochromatic. To bring them to life, artists would delicately apply pigments—often with tiny brushes and sometimes even with breath-blown powders—to give subjects a lifelike appearance. While primitive by today’s standards, these hand-coloured daguerreotypes set the foundation for later developments in colour photography and are an essential part of the exhibition’s narrative.

Another fascinating technique used before true colour photography was possible involved the use of coloured papers and pigment prints. By layering different pigments onto specialised papers, photographers could create images that suggested colour rather than directly capturing it. These pigment prints allowed for a broader range of tonal expression and were particularly favoured in artistic photography circles. This approach was crucial in bridging the gap between black-and-white photography and the advent of fully developed colour processes.

Stereoscopic Images and Hand-Coloured Fairytales

Another captivating element of the exhibition was the use of stereoscopes, which allowed viewers to experience three-dimensional photographs. Many of these stereo images were hand-coloured to create vivid and immersive portrayals of landscapes, cityscapes, and even scenes from fairytales. These images were popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, offering viewers a unique way to experience visual storytelling. Seeing these delicate and carefully coloured stereo photographs, I was struck by how inventive early photographers were in their quest to bring realism and magic to their work.

The Emergence of Pinatypes

One of the lesser-known yet significant methods featured in the exhibition is the pinatype process, developed in the early 20th century. This printing technique involved the use of dyed gelatin reliefs to create full-colour images, making it one of the early attempts at mass-producing colour photographs. Pinatypes offered relatively stable and vibrant hues compared to some of the more delicate colour processes of the time. Although it never became as mainstream as autochromes or later colour films, pinatypes played a crucial role in advancing the commercial viability of colour photography and are a fascinating glimpse into the experimental spirit of early photographic pioneers.

The Pictorialist Aesthetic: Photography as Art

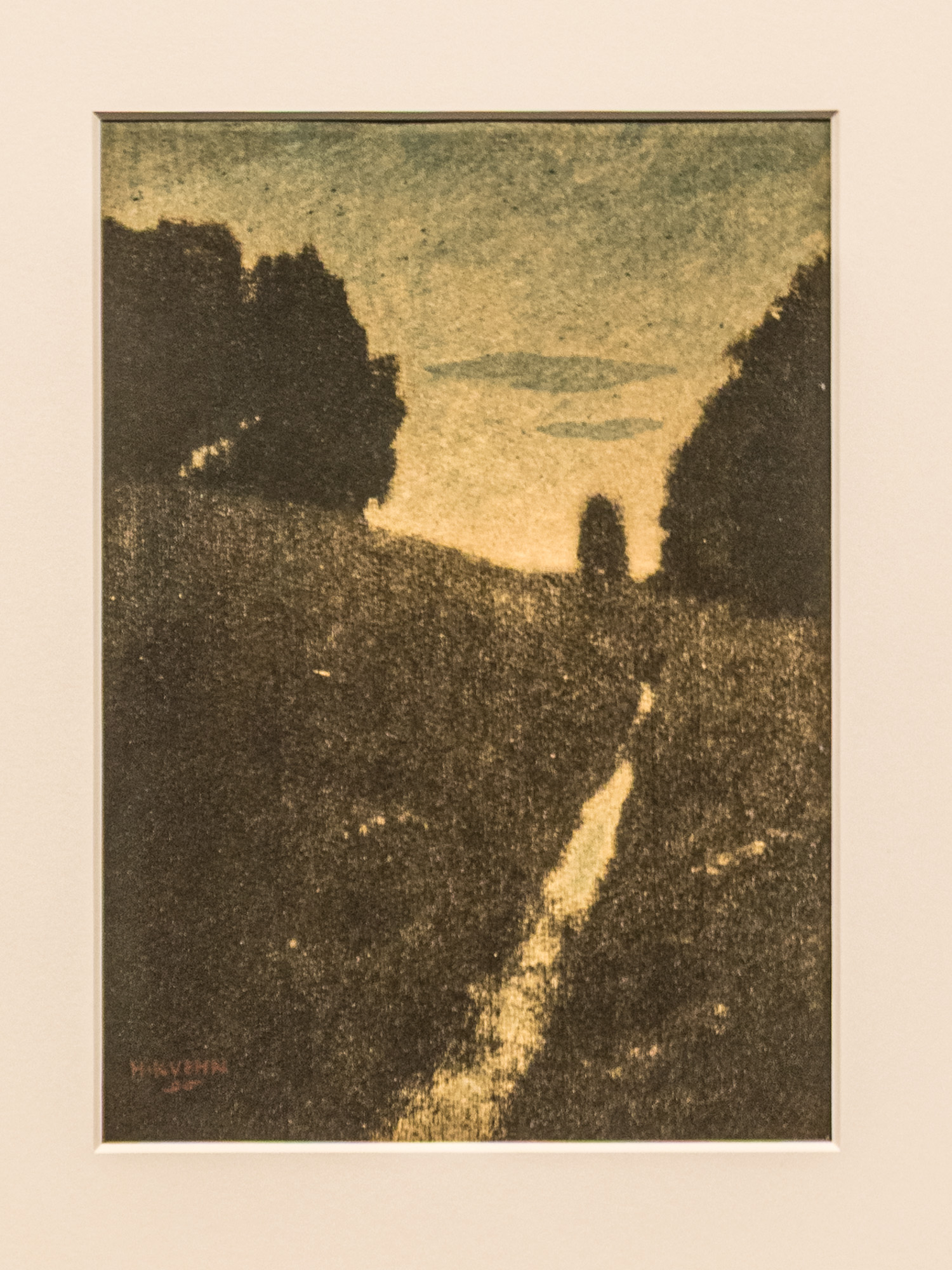

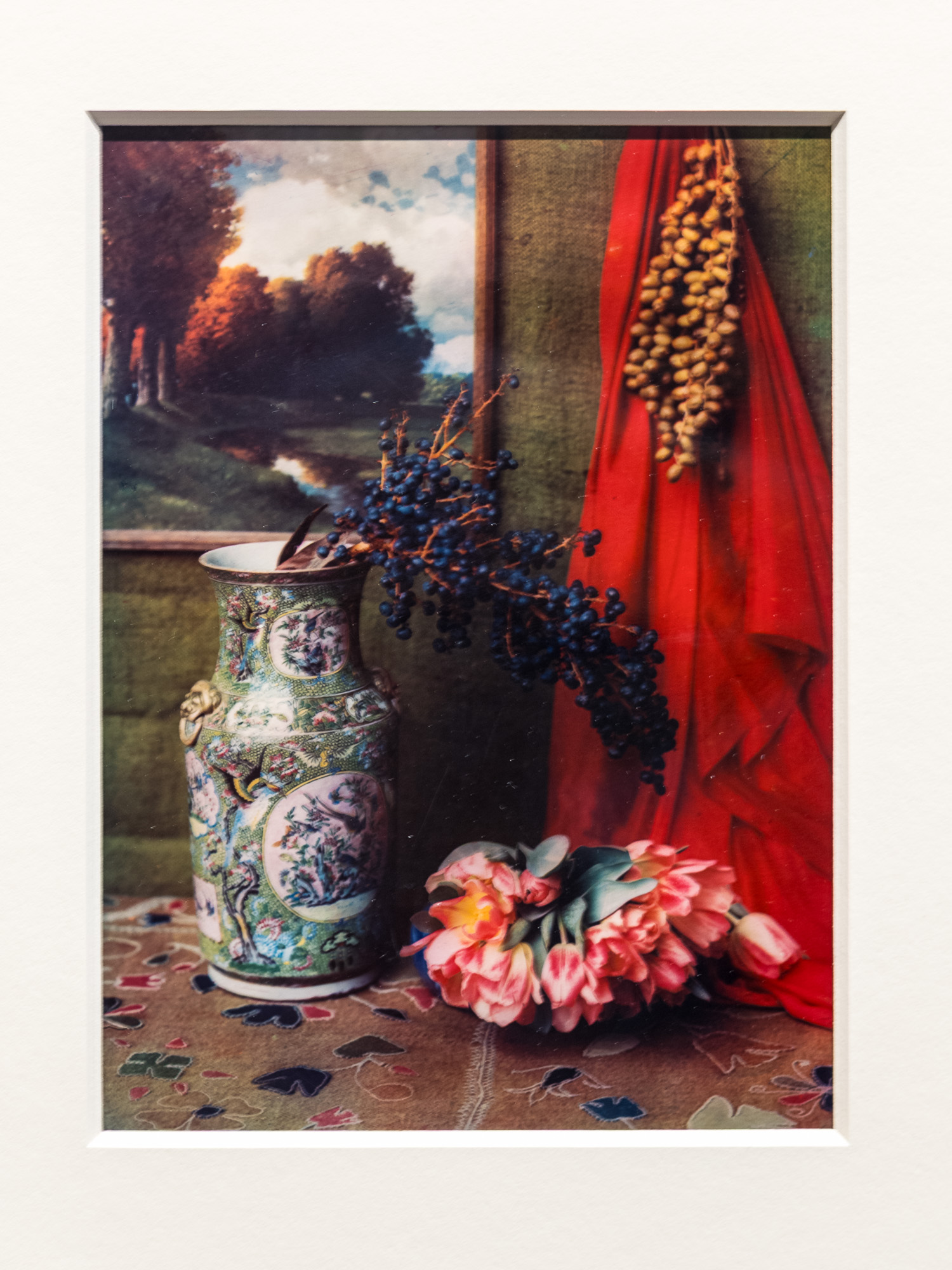

One of my personal highlights from True Colours was the section dedicated to pictorialist photography. Emerging in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, pictorialism sought to elevate photography to the level of fine art, favouring soft focus, painterly compositions, and atmospheric effects. In fact the Albertina modern had a whole exhibition on Pictorialism in 2023, which was a great joy to me.

Heinrich Kühn’s Twilight (1896), produced through the autochrome process, was a standout for me, its subtle gradations of light and shadow creating an almost dreamlike serenity. Kühn was also one of the pioneers of the autochrome process, the first commercially successful colour photography method introduced by the Lumière brothers in 1907. Autochromes used a fine layer of dyed potato starch grains to filter light, creating rich and softly textured images. Kühn masterfully employed this process to enhance the painterly, impressionistic quality of his photographs, further bridging the gap between photography and fine art. Seeing these images up close, I was reminded of how photographers of the past fought for their medium to be recognised as more than mere documentation—it was, and remains, an art form in its own right.

Atelier Dora and the Influence of Female Photographers

The exhibition also highlights the contributions of Atelier Dora, a prominent Viennese photography studio run by Dora Kallmus, also known as Madame d’Ora. Her studio became a hub for creative photographic portraiture, and her work contributed significantly to the development of artistic photography in Vienna. Atelier Dora’s sophisticated approach to portraiture demonstrates how colour and composition could be used to enhance mood and expression in ways that continue to influence photography today.

Richard Neuhauss and the Science of Colour Photography

The exhibition also delves into earlier scientific advancements that played a crucial role in the development of colour photography. A particularly striking example is Richard Neuhauss’s 1906 photograph of a parrot, one of the earliest examples of interferential colour photography. Using glass prisms to manipulate light and capture colour spectrums, Neuhauss was able to create one of the first true-colour images. His experiments with solar spectrums pushed the boundaries of what was thought possible, bridging the gap between science and artistic expression. Seeing his pioneering work alongside more traditional photographic processes underscores just how many different approaches were explored in the quest for accurate colour representation.

The Rise of True Colour Photography

The exhibition seamlessly transitions from these early experiments to the breakthroughs that revolutionised photography. The autochrome process, introduced by the Lumière brothers in 1907, was the first commercially viable colour photography method. The dreamy, slightly grainy texture of autochrome plates made them particularly popular for artistic portraits and landscape photography.

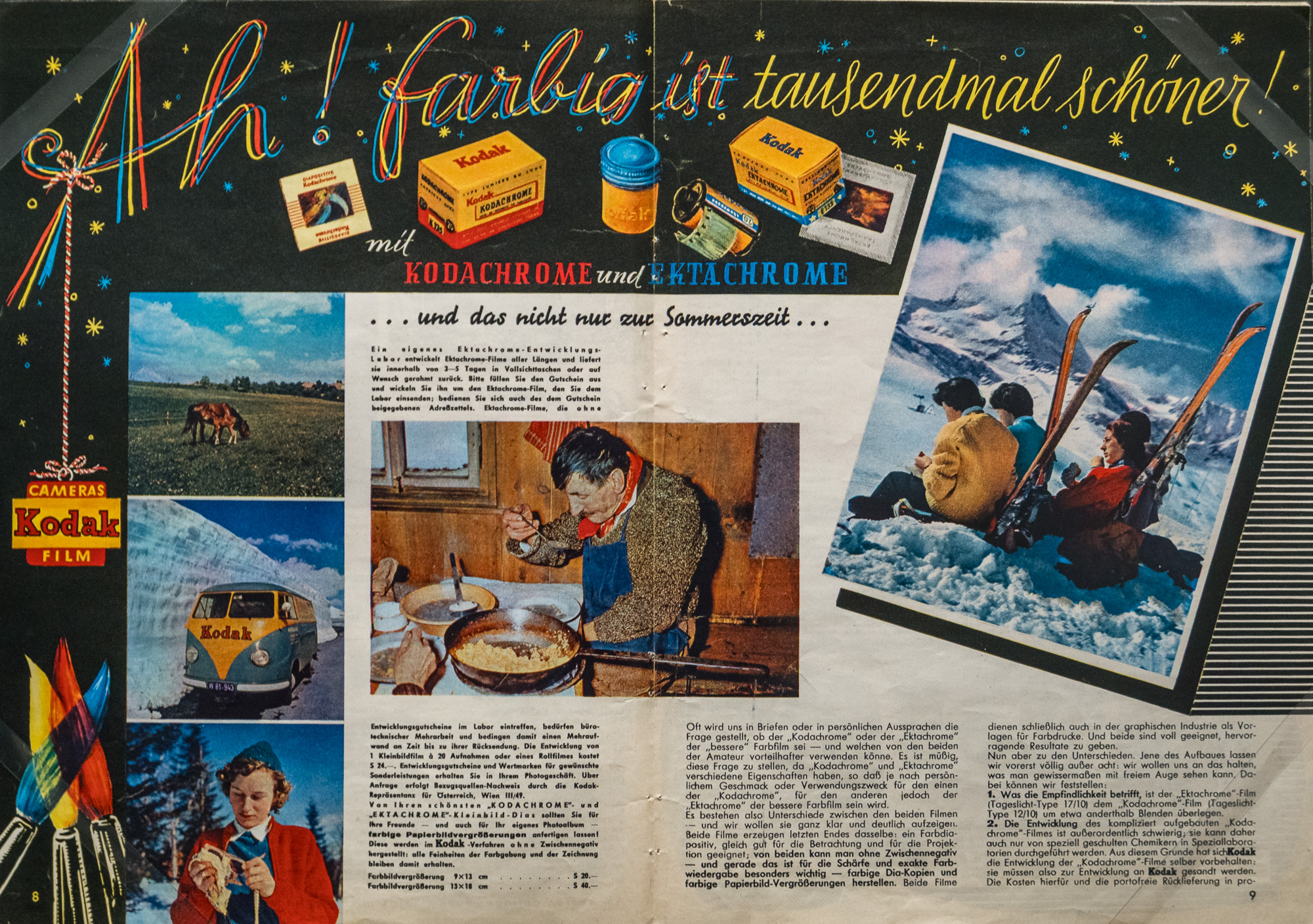

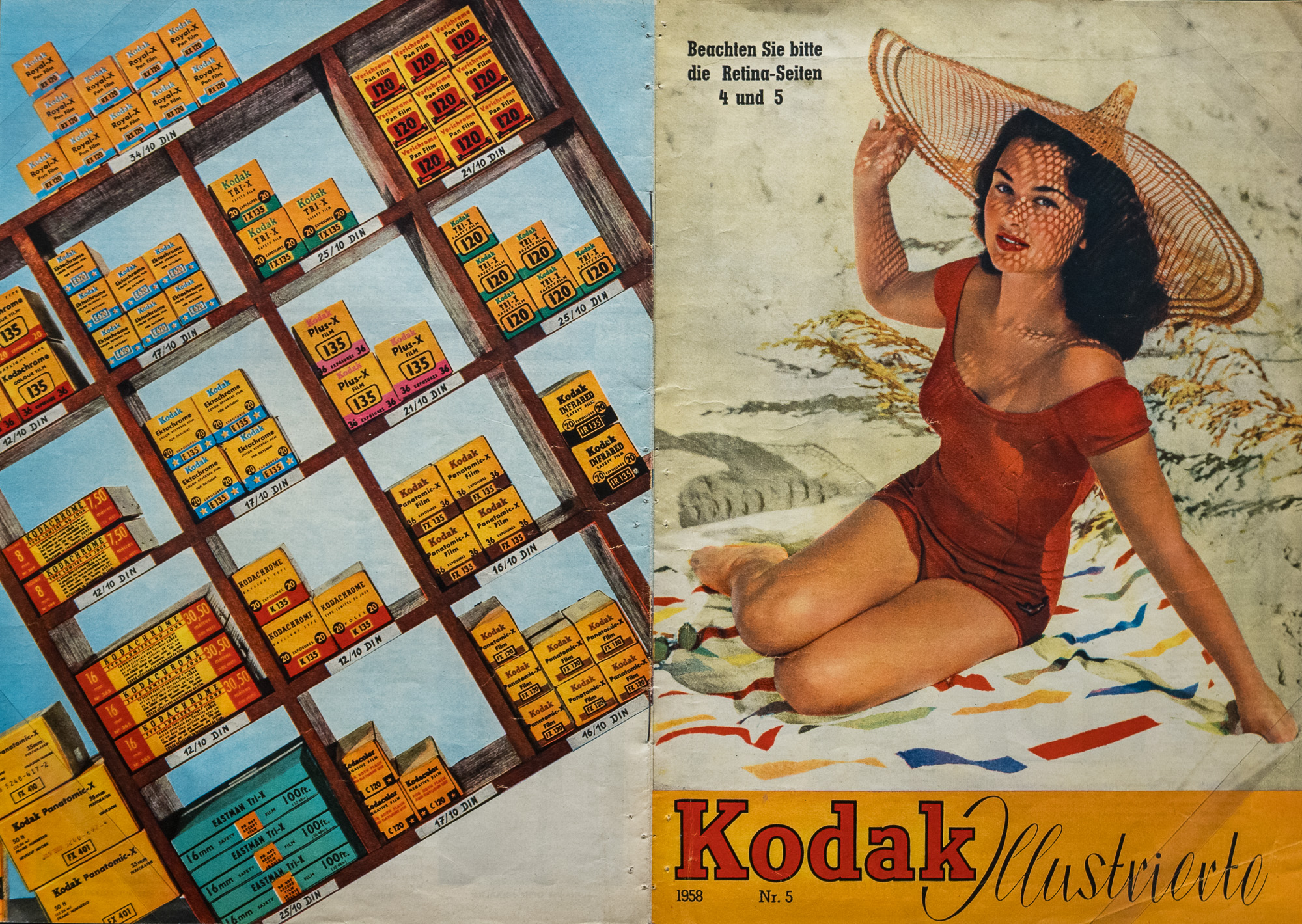

Then came Kodak’s introduction of 35mm colour slide film in 1936, which democratised colour photography, making it accessible to amateurs and professionals alike. By the mid-20th century, colour had become a staple in both artistic and everyday photography, paving the way for the vibrant, high-definition images we take for granted today.

Visiting True Colours is more than just an educational experience—it is a celebration of the artists and inventors who pushed the boundaries of photographic expression. Seeing the history of colour photography unfold before my eyes was nothing short of mesmerising. The exhibition is a must-visit for anyone interested in the history of photography, whether you’re a seasoned photographer, an art lover, or simply someone who appreciates how far we’ve come in capturing the beauty of the world around us.

True Colours is on display at Albertina Modern until 21 April 2025. The museum is open daily from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., and more information can be found on their official website. Don’t miss the chance to step back in time and experience the journey of colour photography firsthand.

EXHIBITION PHOTOS © KARIN SVADLENAK-GOMEZ

[…] Heinrich Kühn (Austrian-German, 1866-1944)Twilight1896Two-tone gum printPhoto: Karin Svadlenak-Gomez […]

LikeLike